| . | CHRISTIANS IN AMERICA BEFORE COLUMBUS

by Richard Graeber

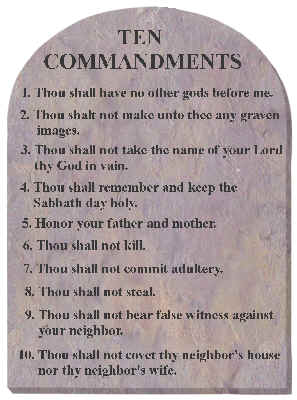

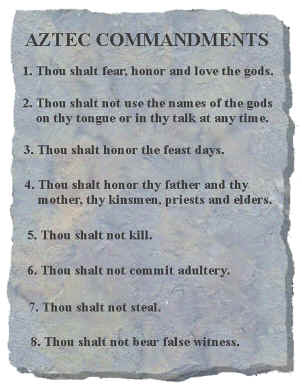

When Spanish Friars first set foot on American soil, they observed and recorded Native religious ceremony and ritual. They were puzzled when they found that indigenous concepts and practices were, in many ways, quite similar to Roman Catholic practices. The natives not only practiced confession and Penance, Lent, Last Rites and Holy Communion, they had their own version of the Ten Commandments, except theirs were eight. The native moral code that was delivered to the citizens at religious ceremonies consisted of eight steadfast rules. When Spanish Friars first set foot on American soil, they observed and recorded Native religious ceremony and ritual. They were puzzled when they found that indigenous concepts and practices were, in many ways, quite similar to Roman Catholic practices. The natives not only practiced confession and Penance, Lent, Last Rites and Holy Communion, they had their own version of the Ten Commandments, except theirs were eight. The native moral code that was delivered to the citizens at religious ceremonies consisted of eight steadfast rules.

At one particular ceremony, Father Diego Duran recorded an oration regarding the Eight Indian Commandments from an Aztec priest in the mid-1500's.

INDIAN COMMANDMENTS:

"Once the solemn rites had terminated, an elder with high authority, one of the dignitaries of the temple, arose. In a resonant voice he then preached words regarding the law and ritual, similar to the Ten Commandments, which we are obliged to keep:

1. Thou shalt fear, honor and love the gods.

The gods were so honored and revered by the natives that any offense against them was paid for with one's life. They held the gods in more fear and reverence than we show to our own God.

2. Thou shalt not use the names of the gods on thy tongue or in thy talk at any time.

3. Thou shalt honor the feast days.

The natives, with a terrible rigor, fulfilled all these ceremonies and rites with fasts and vigils, without exception.

4. Thou shalt honor thy father and thy mother, thy kinsmen, priests and elders.

No nation on earth has held its elders in such fear and reverence as these people. The old father or mother was held in reverence under the pain of death. Above all else these people charged their children to revere elders of any rank or social position. So it was that the priests of the law were esteemed, respected, by old and young, lord and peasant, rich and poor. Old people, in our own wretched times, are no longer honored; they are held in contempt and scorned.

5. Thou shalt not kill.

Homicide was strictly prohibited, but it was not punished by physical death. It was paid with civil death. The murderer was turned over to the widow or to the relatives of the deceased, [to be] forever a slave. He was to serve them and earn a living for the children of the deceased.

6. Thou shalt not commit adultery.

Adultery and fornication were also condemned, to the point that if a man was caught in adultery a rope was thrown about his neck, he was stoned, and [he was] then dragged throughout the entire city. After this the body was cast out of the city to be eaten by wild beasts.

7. Thou shalt not steal.

This commandment was kept in a more rigorous way than it is today, since the thief was either slain or sold for the price of the theft.

8. Thou shalt not bear false witness.

Those people condemned false witness. They punished those caught lying.

Those who had committed these sins and broken the law went about constantly filled with fear, imploring mercy of the gods, asking not to be discovered. Pardon for these sins was granted every four years on the jubilee; their remission took place on the Feast of Tezcatlipoca."

Could the similarities be coincidental? In the absence of conclusive evidence, let's take a look at other similarities in order to help resolve the uncertainties, such as the act of Confession and Cleansing, which were deeply ingrained in Aztec religious practices. Is it a coincidence that Mayans murals show their kings practicing penance centuries before Columbus reached America?

Friar Duran explains the process below.

CONFESSION:

"When I order a penitent to scourge himself, to fast on bread and water, [all the people see the penance], but no one knows the nature of the sin or even suspects it. The same occurred among these people: he who had stolen, fornicated, or killed another or had broken any one of the commandments of laws, the law ordained that he examine his conscience on that day. And in accordance with the number of grave sins he had committed, he gathered the same number of straws the length of the palm of a hand, such as those used for brooms. After having counted his sins with those straws, he went to the temple at the hour when the others had gone to bathe. He squatted before the goddess; he took a pointed instrument and passed it through his tongue. When the piercing of the tongue had been accomplished, he picked up the straws and one by one passed them through the hole: and as he pulled each through, he cast it, full of blood, before the idol. All those present knew that if he cast down ten straws he had committed ten sins, and if twenty, twenty; but they did not know the nature of these sins. In this way they confessed their sins before the gods and the priests and then went to bathe like the rest and eat food we have described. These penitents who confessed were numerous, both men and women.'

"When the sinners had finished their penance and confession, the priests gathered the bloody straws, went to the Divine Hearth, and burned them there. With this, everyone felt cleansed and pardoned for his transgressions and sins, having the same faith that we hold for the Divine Sacrament of Penance."

Father Duran further explains the indigenous ritual methods of the practice of Aztec communion.

HOLY COMMUNION:

"I do not wish to be repetitious, but, since our subject requires it, I must explain this term in case someone has forgotten what tzoalli is. It is bread made by the natives from amaranth seed and corn grains, kneaded with dark honey, a thing highly esteemed by them. Today it is eaten as candy. In olden times [tzoalli] was held in great reverence and was the material with which the [images of the] gods were made. After these had been worshipped and sacrifices and ceremonies had been performed before them, [the bread]. In pieces, was distributed and was partaken of as the flesh of God, and all received communion with it, having first washed by order of the priest.'

"Purification by washing was a most common thing when ordered by the priests. If a person went to tell the priests about his own illness or that of his child or spouse, the following prescription was given to him: he was to grind that seed, knead it with corn, and mix it with honey; but first he must wash, purify himself of his sins, and then go eat [tzoalli]. This sounds somewhat like advise from Christian physicians on the first day they see their patient. Before beginning the treatment, they ask that he confess and receive communion. So it was that this day [the natives] confessed and received communion, as I have said."

To some of the Christian Friars the similarities they found were unsettling. The Aztecs were found to be very chaste people. Were the religious practices of the Aztecs influenced by exposure to the Spanish invaders?

According to a former priestess in the native hierarchy, the Christians didn't bring anything new. The Aztecs practiced Lent and fasting before exposure to Spanish Christianity. Their dead were laid to rest after preparing the soul to reach the place of eternal peace. There was also a hell. Father Duran recorded the exchange.

" Once an old Indian woman, wise in the ancient ways, perhaps a former priestess, was brought to me. She told me that in ancient times the natives had Easter, Christmas and Corpus Christi, just as we do, and on the same dates, and she pointed out other very important native feasts, which coincide with our celebrations. 'Evil old woman,' I said, 'the devil has plotted and has sown tares with the wheat so that you will never learn the truth!"

In retrospect, it could be interpreted that the good friar was guilty of his own accusations.

Within the same time frame, Cabeza de Vaca, a soldier and explorer, was stranded amongst the natives of the Gulf Coast, Florida, Texas and Arizona, for eight years. During his quest to convert the Indians to Christianity, he was surprised by the Indians' answers to his questions regarding their own religious beliefs. When asked to repeat the teachings of Christian ideology, as they understood them, the Indians gave their response. and Arizona, for eight years. During his quest to convert the Indians to Christianity, he was surprised by the Indians' answers to his questions regarding their own religious beliefs. When asked to repeat the teachings of Christian ideology, as they understood them, the Indians gave their response.

"To this they replied through the interpreter that they would be very good Christians and serve God. Upon being asked whom they worshipped and to whom they offered sacrifices, to whom they prayed for health and water for the fields, they said, to a man in Heaven. We asked what was his name, and they said Aguar, and that they believed he had created the world and everything in it.'

"We again asked how they came to know this, and they said their fathers and grandfathers had told them, and they had known it for a very long time; that water and all good things came from him. We explained that this being of whom they spoke was the same we called God, and that thereafter they should give Him that name and worship and serve Him as we commanded, when they would fare very well."

De Vaca traveled through many towns in an area currently known as Texas and Arizona. Even though each Indian clan hailed by different names, their bonds extended thousands of miles; they all spoke the language of the Aztecs. The explorer mentioned in his chronicle receiving a curious rattle from the natives.

"There, among other things which they gave us, Andres Dorantes got a big rattle of copper, large, on which was represented a face, and which they held in great esteem. They said it had been obtained from some of their neighbors. Upon asking these whence it had come, they claimed to have brought it from the north, where there was much of it and highly prized. We understood that, wherever it might have come from, there must be foundries, and that metal was cast in molds."

The people that became known as the Aztecs originally resided in the "Four Corners" area of New Mexico. This is where the Chaco Canyon became a major metropolitan center for western North America in the first millennium AD. A fifty-year drought devastated the area in the middle of the eleventh century. The Mexica (aka: Aztecs), one of a group of seven tribes, left behind the Hopi (peaceful ones) for a better life further south.

Chaco Canyon was connected to the Great Lakes region via the Hopewell Highway. The native people would travel thousands of miles for trade or on pilgrimage. To the southwest of Teotihuacan in central Mexico, where the Pyramid of the Sun exists today, are the ancient remains of Tula, the Toltec capital. Found there are native paintings of a Toltec priest depicted with red hair and very pale skin that sunburned. Maybe his physical characteristics are just a fluke of nature, since he was purported to have native parents. It was this Toltec holy man and his followers, after leaving the Mexico basin around 1100AD, that built Chichen Itza on the Yucatan peninsula.

The Toltec holy man, Ce Atl Topiltzin Quetzalcoatl*, was persecuted and banished from his homelands by a competing religious sect. He was said to have walked to the eastern coast marking his path with miracles and the sign-of-the-cross to denote his route. As a matter of fact, the Spanish padres found the indigenous crucifix symbol all over "New Spain".

If the Spanish friars were totally biased and unreliable in the accounts laid down in their chronicles, any similarities chronicled between the Native and European cultures would be merely a matter of interpretation. It has been argued that the figure of crossed lines that make up a crucifix is easy for anybody to invent and that it has been used by various cultures for various purposes throughout time. And, the fact that a fair-skinned, red-haired Toltec priest marked his way to the sea with that symbol means nothing.

The consuming question of the hour is; how did the Aztecs develop a set of religious practices nearly identical to the methods and teachings of the Catholic Church? Coincidence could explain maybe one or two similarities. In light of the recent discovery of the Mauritanian treasure trove (see Issue #30) found in Illinois, there are strong indications of Mediterranean cultural influence in ancient America. So the question becomes: Did the Mauritanians bring Christianity to the Americas fourteen and a half centuries before Columbus and were the Aztec religious customs influenced by their ancestors' exposure to that?

Were the Spanish friars totally biased and unreliable in the accounts laid down in their chronicles? Are any similarities between the Native and European cultures merely a matter of interpretation? The latest evidence doesn't actually clarify the picture, but adds another scenario to a list of inconclusive possibilities.

The Hebrew Genesis describes a great flood that destroyed the world. The Aztec Calendar contains a similar account. According to the native legend, we are living in the age of the Fifth Sun. It is told that this age will end when "earthquakes destroy the world." Four past ages that ended violently with the destruction of mankind have preceded this current age. The epoch known as the Fourth Sun was called "The Age of Navigation", implying a maritime emphasis. It is said to have ended when the formerly mentioned flooding waters engulfed the world.

According to Mayas, who preceeded the Aztecs, the "Beginning of Time" started in 3113BC. This was the beginning of a 5125-year cycle that will end in the year 2012AD. Is this connected to the "End of Days" as mentioned in the Old Testament? Or, does it relate to the Hopi legend that describes the return of a portentous "blue star?" Since the bulk of Native American libraries and corresponding knowledge have been obliterated by Christian zealots, we can only wait and see.

*Ce Atl is an Aztec word that means "One Water." There is a town is Washington state by the same name, i.e.: Seattle.

References:

Caso, Alfonso.

The Aztecs, People of the Sun.

Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press, 1958.

Cabeza De Vaca, Alvar Nuñez

The Journey of Alvar Nuñez Cabeza De Vaca, 1542.

Translated by Fanny Bandelier (1905)

PBS, Archives of the West

Alexandria, Virginia

Duran, Friar Diego.

Book of the Gods and Rites and the Ancient Calendar, 1581.

translated from Spanish.

Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press, 1971.

Gilmore, Frances

The King Danced in the Market Place

Tucson, Arizona: University of Arizona Press, 1964

Sahagun, Friar Bernardino de

Historia General de las Cosas de Nueva Espana. 1545. Vol. 4, 2nd ed.

(edited by Garibay Kintana)

Mexico: Editorial Porra, S. A., 1969. copyright © 2001, Historical Science Publishing |